Black Blog Review: Ijaw Girl

This week, I’ll share with you a blog I stumbled up. I was interested in reading Ijaw Girl because I myself am half-Ijaw. I expected a blog about the struggle of the Ijaw in the Niger Delta against oil companies, pollution, and violence but what I got was…FASHION!

Ijaw Girl should really be called Nigerian Fashionista. The subtitle for the blog is:

-for the love of all things bright,beautiful & tailor made. -celebrating nigerians in and around fashion.

Ijaw Girl is the blog of the designer of the label AKPOS OKUDU. She is also a student. Her profile sets the tone for the whole blog:

i’m a fashion designer who loves quirkyness,couture dresses,red lipstick,photography,sewing with really loud music,dressing my friends,cocktail rings,sexy lingere,d big apple,shoes,u2,oprah,sex& d city,bags,beyonce,blush,vogue,red nail polish,the cranberries,d colour green,norah jones,playin dress up. i also love dancing in front of d mirror,bono,my beauty sleep,flats,lucite& vintage bangles,recycling trends,kate moss,eco chic[lets do our bit 2 help save d planet],thisday style,my fab. cousins[my inspiration]style.com,old hollywood movies,chandellier earrings,paris and most importantly my gap joca jellies.

This blog is about Nigerian Fashion and although I was hoping to read the blog of a politically aware Ijaw Nigerian woman, it was interesting to read about the Nigerian Fashion scene. The blog is full of images of Nigerian Fashion, as well as the blog writer’s own work.

I was fascinated to learn about the reinvention of Ankara Fabric in Ijaw Girl’s post “Nigerian Designers Jazz up Ankara“. Ankara fabric originally came from Europe (but the Turks made a cheaper version so that is why it is called Ankara, after the Turkish city of the same name). Nigerians loved the fabric and began making their own elaborate culturally inspired designs on it. But for a long time, Ankara Fabric was only associated with traditional and “frumpy” Nigerian clothing. Now Ankara Fabric has become chic, and most Nigerian fashion designers have a line of Ankara dresses and accessories. According to Ijaw Girl “An Ankara outfit is definitely a must in every fashionista’s closet”. To learn more about the history of Ankara in Nigeria read the article “Ankara: The Rebirth” in fashionafrica.com.

Nigerian women are super fabulous; i know, i know.i could say that a million times. Your probably sick of hearing it; but come on this is a blog that generally celebrates fabulous Nigerian fashion and pretty much anything fashion related.

As amazing as i consider Nigerian women stylewise, there are lots who generally go over the top with their outfits;so when i find pictures of Nigerian women that look on point you know I’m drawn to them like a complete magpie and i get super excited.

African Writer Profile: Dayo Forster

Dayo Forster

Dayo comes from a family of Aku, otherwise known as Krios. The Aku originated from Krios who came from Sierra Leone in the 19th Century. The Krio are a mixture of recently freed slaves who were liberated from slave ships intercepted by the British in West Africa and freed slaves returning from the diaspora from such places as the US, the Caribbean and Nova Scotia. Many of the freed slaves were of Yoruba descent, which is why it is common to find Krios with Yoruba names, like Dayo.

Dayo studied statistics and computing at the London School of Economics.

Dayo had always been an avid reader but she took up writing late in life.

On her website she writes:

I took up writing aged 35, while living in America, essentially to figure out a way of expressing opinions and publishing essays on various topics. I stumbled into fiction while attending a writing workshop. The optional assignment was to extend a character in a story someone else had written. I tried it – and was bowled over by the power of virtual reality – the ability to create someone else’s world and be able to view everything through that person’s eyes. And to feel God-like, able to make things happen, yet be sensitive enough to continue to inhabit a character’s skin.

To learn more about Dayo’s relationship with literature, read her piece “a short life in literature”.

Dayo went on to publish a short story in Kwani?, a Kenyan literary journal. She would later participate in the 2006 Caine African Writer’s Workshop. The short story she wrote for the workshop would be published in the 2006 Caine Prize for African Writing Anthology, The Obituary Tango. The short story she wrote for Kwani? would lead her to write her first novel, “Reading the Ceiling”.

“Reading the Ceiling” follows the three possible trajectories that the life of its heroine, Ayodele, could take based on who she chooses to lose her virginity to when she is 18 years old.

Dayo is the first Gambian woman to get an international publishing contract. She was able to achieve this with the help of her contacts in the Kenyan literary scene.

In her interview with Molara Wood she says:

In Kenya where I’m based, I went along to monthly meetings organised by Kwani? I read the first chapter of my manuscript and got lots of helpful feedback. Binyavanga Wainaina (2002 Caine winner and Kwani? founder) recommended some agents; the first one I contacted, signed me. I wrote the first draft while in the US, in 4 months; the whole process was wonderful and quick. If I hadn’t been living in Kenya, it would have been difficult to complete this book. I do thank Kenya for that. There were a few people who were selfless.

“Reading the Ceiling” was shortlisted for Best First Book in the 2008 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize-Africa Region.

Dayo Forster speaks Krio, Wolof, Kiswahili and French.

She is currently working on her second novel.

Further Reading:

An Interview with Dayo Forster about her book “Reading the Ceiling” from African Loft

An Interview with Dayo Forster by Nigerian writer Molara Wood

Black Blog Review: The Missing Piece…thoughts of a black adoptee

This week, I am reviewing the blog The Missing Piece…thoughts of a black adoptee

The author of the blog describes herself as:

black woman, adopted into a white family as an infant; mother of 2 girls; part-time insomniac; ex-lawyer; interests include: family stories, culture, race, books, writing, art, parenting, other adoptees, gardening…

In the post “who am I?”, the author gives more details about her home life.

The author of The Missing Piece was born in Nova Scotia, Canada, and adopted into a White family. She does not know her biological parents, but she does know that her mother is White and her father is Black.

In the post, Rejection: adoptee woes in a nutshell, she writes about her struggle to contact her biological mother and get the name of her biological father. The post is a fascinating tour through Nova Scotian Adoption Legislation, for example, because her biological father never acknowledged paternity he is not legally her Birth Father.

In the post Missing Pieces, she explains her choice of blog name:

I don’t mean to characterize adoptees or transracial adoptees as ‘missing pieces’ or incomplete human beings, so just hear me out. An old, true friend introduced me to The Missing Piece, by Shel Silverstein many years ago. It succinctly and beautifully sums up the road many of us take to find ourselves, but especially adoptees who might feel at different times in their lives that they are missing some crucial part of themselves – knowledge of self, knowledge of family, medical or cultural history.

I really enjoy The Missing Piece blog because although I was not adopted, having a deported Black father who I had no hope of finding, and growing up in my mother’s totally dysfunctional White family, often made me feel like I was an orphan.

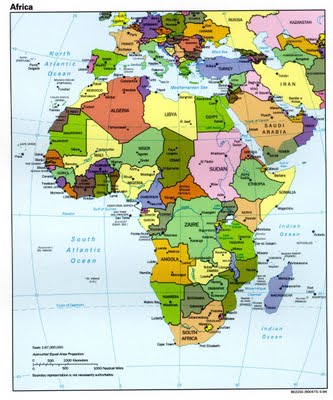

I can particularly relate to her struggles with Black Identity. In her post Back to Africa, she writes:

As a black girl growing up in a white family I was often on the outside of black culture and community. That is, until I entered junior high and made black friends, listened to black music, read black history and literature and deliberately absorbed black culture. Embracing black culture gave me some self-confidence and generally helped in the quest to know myself, but a kind of doubtful self-consciousness about my cultural identity remains. I am easily shaken if someone (black or white) insinuates I am not black enough, because I am too fair-skinned, or because I like to read, or because my family is white, or for some other ridiculous reason. What do you care what other people think, my friends and family ask. Intellectually I know I should not care, but the emotional need to belong or fit within family and community is strong.

I too grew up isolated from Black communities. In someways, the author is lucky to have grown up in Nova Scotia, which has a large and deep-rooted Black community. Growing up in Ottawa, in the 80s and 90s meant that I didn’t have much opportunity to interact with Black people, until the wave of Somali immigration in the mid-nineties. I can’t say I have ever really “embraced” Black culture because I don’t think there is such a thing. I am grateful for finally learning how to manage my hair (which shows no signs of being mixed as it is quite short and course), something I only accomplished in my early twenties with the help of a friend of Afro-Trinidadian descent. Here in Ottawa, there are now large communities of Sub-Saharan African descent but they are divided by ethnicity, culture, religion, and language (Ottawa is a bilingual city) so you can hardly say there is a Black Culture here. But I do interact a lot with these communities, some more than others (for obvious reasons I am closer to Muslim communities, but I find that I get on well with both Muslims and Christians from the Horn of Africa, and with Muslim and Christian francophones. Ironically, I seem to get on the least with Nigerians of any ethnicity, despite the fact that I am ethnically half-Nigerian. I guess a sense of belonging has very little to do with bloodlines).

I think many of the author’s issues with Black Identity are the same for all of us who are mixed race but didn’t grow up with our Black parents.

They are many Black adoptees out there. The Missing Piece’s blog roll contains links to other websites and blogs by transracial adoptees, as well as a link to the Black Adoptees Group on Facebook.

I learned from the Missing Piece blog that Darry McDaniels, the DMC from Run DMC, is a Black Adoptee, as well as musician Michael Franti. I am also grateful to the author for highlighting the work of Jackie Kay, a Black Scottish writer who was adopted into a White family. Kay’s father, like mine, is a Nigerian. She had the opportunity to meet him but it did not turn out as hoped, because he was hell bent on trying to save her soul by converting her to his rabid form of Christianity. This was actually my big fear when I found my father. As so many Nigerians I had met seemed to detest my conversion to Islam, I was worried my father might reject me because I was a Muslim or make our relationship contingent upon me becoming a Christian. I am grateful that this was not the case.

I hope the author of The Missing Piece continues to write about her own struggle, as well as the struggle of others to piece together the puzzle of mixed race and transracial identities.

Poem: Spirit of the Wind by Gabriel Okara

Spirit of the Wind by Gabriel Okara

The storks are coming now

white specks in the silent sky.

They had gone north seeking

fairer climes to build their homes

when here was raining.

They are back with me now

spirits of the wind,

beyond the gods’ confining hands

they go north and west and east,

instinct guiding.

But willed by the gods

I’m sitting on this rock

watching them come and go

from sunrise to sundown,

with the spirit urging within.

And urging, a red pool stirs,

and each ripple is

the instinct’s vital call,

a desire in a million cells

confined.

O God of the gods and me,

shall I not heed

this prayer-bell call,

the noon angelus,

because my stork is caged

in singed hair and dark skin?

Poem: The Call of the River Nun by Gabriel Okara

This is Gabriel Okara’s famous poem.

The Nun is formed when the Niger River splits in two, forming the Nun and Forcados rivers. This poem is all the more poignant now to Ijaws because Shell is dredging the River Nun .

The Call of the River Nun

I hear your call!

I hear it far away;

I hear it break the circle of these crouching hills.

I want to view your face again and feel your cold embrace;

or at your brim to set myself and inhale your breath;

or like the trees, to watch my mirrored self unfold and span my days with song from the lips of dawn.

I hear your lapping call!

I hear it coming through; invoking the ghost of a child listening, where river birds hail your silver-surfaced flow.

My river’s calling too!

Its ceaseless flow impels my found’ring canoe down its inevitable course.

And each dying year brings near the sea-bird call, the final call that stills the crested waves and breaks in two the curtain of silence of my upturned canoe.

O incomprehensible God!

Shall my pilot be my inborn stars to that final call to Thee.

O my river’s complex course?

Further Reading:

Interview with Gabriel Okara, an Ijaw Writer

I want to devout a large portion of my blog to sharing my knowledge of Nigerian History, Literature and Culture with my readers.

Nigerian Literature is probably more well known internationally than the literature of other African countries but it is still not read a much as it should be.

This article is a great interview with a famous Ijaw writer, Gabriel Okara, which originally appeared in the Nigerian Sun News Online.

It’s also a great survey of some pivotal events in Nigerian History, such as the Biafran War.

My father met Okara’s daughter and through her I was able to have a short exchange through e-mail with Gabriel Okara himself. I intend to write a review of his novel, The Voice, soon for my blog.

Unfortunately, this article also highlights the lack of financial support given to Nigeria’s great artists.

Writer saw me pushing my old car and Gov gave me a new one -Gabriel Okara

By NWAGBO NNENYELIKE

Tuesday, March 16, 2004

Although he has just 17 years left to become a centenarian, Gabriel Okara, the great African poet, is still very active and agile. The octogenarian writer, whose poem, The Call of the River Nun, won the best literature award 51 years ago in the Nigerian Festival of Arts, developed his writing career through self-education and reading. This took him to several libraries, including that of Oxford University, England. The outcome of this reading habit made him one of the main literary figures not only in his country and Africa, but also around the globe.

The Ijaw-born poet, who is reputed for projecting African world-view, has also argued in favour of indigenous languages. He has reasoned that English language can be well manipulated to express African cultural values. This is what he experiments in his popular novel, The Voice.

Many of his poems are embedded with Ijaw imageries and symbols. And because he abhors injustice in whatever form, the poet told Daily Sun that he stood on the side of Biafra during the civil war as a propaganda officer and later, as the poet who was able to write so many war poems.

Background

I was born in 1921 at Boumandi in Bayelsa State. I attended the village school and also primary school in Kaiama from where I was awarded government scholarship to Government College, Umuahia. I left the college in 1940. That was during the Second World War. I had wanted to join the Air Force but because I failed the medical test, I joined the British Airways. I was transferred to the Gambia from where I came back to Nigeria. I have been a widower for many years. My wife died in 1983. Remarry? Oh! I do not want to talk about that but I have four children.

Information service/Journalism

All the while I was in the Airways, I was reading and writing. Then when I came to Nigeria from the Gambia, I joined the media. It was in Enugu when my poem, The Call of the River Nun, won the best award for literature in Nigeria Festival of Arts in 1953. From then, I continued writing. I later became the information officer in the Eastern Regional Government. I ran a number of courses in British Information Services Centre, London. Also, I was in Northwestern University, USA where I studied Comparative Journalism and Public Relations. That was a special programme for foreign journalists.

My role in the civil war

I was the head of the information service when the civil war broke out. I was on the side of Biafra, tagged the rebels. I wrote many war poems some of which were included in my first poetry book, The Fisherman’s Invocation, which won the Commonwealth prize in 1979. I did not go to the warfront as a soldier. I was the director of the cultural division of the Propaganda Directorate. I worked with Comrade Uche Chukwumerije and Dr. Eke. I have not heard much of Eke now, but they were the top directors.

Biafran intellectuals/Emeka Ojukwu

They were those attuned intellectually to the course of Biafra, because they were convinced that it was a right and just course. People like Chinua Achebe, Cyprian Ekwensi and myself who is not an Igbo and many others. The Biafran leader, Emeka Ojukwu, sent three of us to the US during the war to tell the world about the fate of Biafra. This was to let the world know that it was not just soldiers but that intellectuals joined in the fight, too. We read our literary works during the tour.

After the war

I was absorbed back into the civil service which had by then been created. I set up the Rivers State newspaper, The Tide, from scratch. Again, I set up Rivers State Television. I became commissioner for Information and Broadcasting in 1975.

How I started

I was propelled by the interest in writing, reading and the curiosity to know. Early in life, I knew I was going to write even as I was at the Government College, Umuahia. In fact I thought I was going to be a Fine Artists. I painted so well in water colour. But later I came to realise that I’m more talented in writing poetry. So I started and continued with it. I cannot remember the first poem I ever wrote but I wrote, a lot and even short stories till the time I wrote the poem that won the literature award in 1953.

The Call of the River Nun

In this poem, I was trying to remember my life as a child born at the bank of River Nun; how peaceful, joyous and beautiful life was at that time. Then coming into life as an adult in a strange place like Enugu, I found that things were not what I thought they would be. As a child, everything was rosy and beautiful. But as an adult, I came face to face with the realities of life and the various challenges people contend with. People follow unscrupulous ways to get along, shoving other people aside in a crowd to move on. It became a matter of survival of the fittest.

Ijaw/riverine world view

Ijaw man does everything of his in the water. He derives his livelihood in the river and other water related things. His way of life is the water. That is his culture.

African Literature

There are about three schools of thought as to what African literature is. One said you do not have to write in a special way that your Africaness would emerge with respect to what you write in any foreign language. The other group went to the extreme to argue that the only authentic African Literature must be written in the indigenous language of the writer. Mine is the mid-way. We can adapt the metropolitan language, but use it in such a way that it will suit our own way and the idea we want to express in our own language. That is the result you find in my novel, The Voice.

Inspiration

It is all about being very sensitive to what happens around me. I see things in the way that others would not see them. For instance, in my ideal country, I think of a corruption-free country because it is corruption that pervades all sectors of the society. The reality of corruption in the society conflicts with my own corruption-free society. It is like singing. What makes the singer sing may be the feeling of joy or sorrow. This feeling can equally be expressed in poetry or in prose. So I have, in most cases, expressed my feeling using poems.

Symbols and images

I use them a lot in my poems. The Fisherman’s Invocation, for example, is full of symbolism. I am talking about the gaining of our desire, the independence. That is the fight for victory. After the victory dance and the palm wine in the head, we have to face governance. In the poem, I have used the reverie Ijaw symbols and images as well as tradition to present the experience. In most cases, I use universal imageries. For instance, in the same The Fisherman’s Invocation, I used Midwife which is known everywhere. That is to say that when you write, your culture is bound to reflect and also universal culture.

Block

At times people want to write, but it will not flow. In my own case, it does not happen very often Whenever it happens I leave that particular piece to sleep for days, weeks, months and even for years before I start it again. But I will be writing other things. My best writing time is in the night.

He was a very good friend of mine. We used to gather, form a poetry group, read and criticise our poems. That was when we were all young. Apart from poems, we used to talk about the state of the nation. Wole Soyinka used to be in the group.

Writing for children

I write for children just like Chinua Achebe does. We all learnt a lot in Government College, Umuahia. But Achebe and the rest of them were my juniors. Most of the teachers that taught us were young graduates from Oxford and Cambridge who were very sound. The library was filled with books. So I feel that it is to nurture the reading as well as writing habit of children which I equally acquired in the college by writing for them. It will also help to implant the idea of honesty, bravery, hard work and good behaviour while they are young because most of us imbibed same as children. Apart from school, my father taught me early in life that it is better to tell the truth and die than to live in falsehood. And that if I must be anything in life, I must work hard for it. These have been my guiding principles.

State of Nigerian writers

Many people work, retire and live on pension. But the case of writers is quite different because they are independent. Writers are self-employed and live by our writing. That is the only thing we have. We gain very little in terms of cash reward. This is because many people stop reading immediately they leave school. In fact, generally, poets do not have money. Only textbook writers make money these days because their works are used in school. But then the money they make is still small. Ours is if the Ministry of Education recommends our creative work, you make money during that period. When the book is no longer required, nothing again. Worst still, there is the case of piracy. Of course, the copyright law is not effective because nobody is really enforcing it.

State of poetry in Nigeria

There are some young writers whose poems are good. But many also have wrong ideas about poetry. They feel they will not make money by writing poems. So when they are in school, they ask what are they going to do with poetry when they leave school. They conclude that with something like Engineering or Law, they can make money. As such, they do not develop interest in poetry. Indeed, the state of poetry is that people do not read poems for the sake of reading them but for examinations. Many people do not read at all. Some think that poetry is a foreign thing. I ran a class in Imo State University and I told the students that poetry exists with us, that we have it in our villages. The traditional songs we sing and ballads are all poetry. And that is how poetry started in Europe before it was written down. I told them to write down in the native language some of their traditional songs like dirges, the songs at marriages and other events. They did and I asked them to read and sing them. Later I asked them to translate them to English. After the exercise, they were all happy. They accompanied these songs with dances. Of course, in African tradition, songs go with dance. You cannot stand still when you sing as the Europeans do. It was a great revelation to them.

Literature in Nigeria

There is a wrong idea about literature in this country, especially among the youths. They think that anything written is publishable. I am saying this out of experience. Many bring what they have written for me to help them get a publisher. But publishing companies are commercial enterprises. They want to make money out of what a writer has written and give him a certain percentage. So it is not easy for some works to be published. But those who have the urge to write should continue. Opportunity would surely come for the publishers or the general public to discover them.

Car gift to me

The Executive Governor of Bayelsa State, Chief Diepriye Alamieyeseigha, presented a brand new 406 Peugeot to me on my birthday. I was told that the Secretary-General of Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA), Bayelsa State branch, told the governor that he saw me pushing my old car trying to get it started along the street. The governor was touched as to why a great man like me push a car when I should ride comfortably in my car. I am grateful to the governor for that kind gesture.

My coming volume

My next volume of poems is with the publishers in the US. The title is, The Dreams, His Vision. I chose that title because most of the poems are about debacle and suffering under the military dictatorship. The dreamer is a man who dreamt about the future of his country and joined the mass movement of the people, became a leader of the masses and was overthrown by the dictators. The dreamer is somebody who would come and deliver this nation from the grip of military dictatorship. What made me use the title is Moshood Abiola. When he was campaigning for the presidency, he said, “You the people of this country have made me what I am today. And I am going to give you back when I become the president.’’ I respected him for that statement which is a great dream, but he never lived to realise it. So he is the dreamer in that poem.

My publications

The books I have written are, The Fisherman’s Invocation (poetry), The Voice (prose), and a lot of books on children, like Little Snakes and Little Frog.

Further Reading:

The Voice, a novel by Gabriel Okara

1 comment